The electrification imperative

How a switch from burning fossil fuels to using electricity can unlock the full value of the energy transition

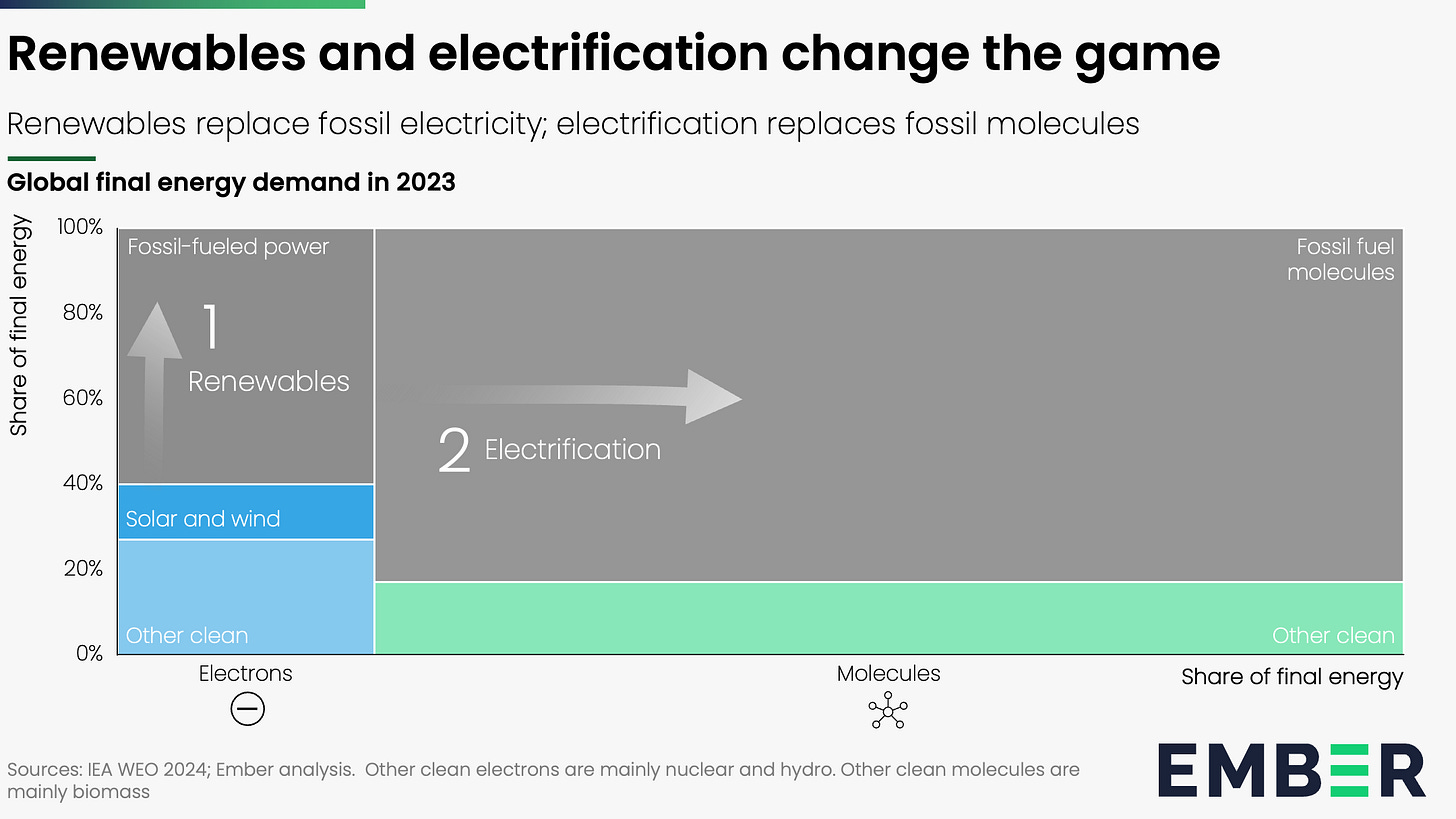

There are two key races in the energy transition. The renewables race to generate electricity, and the electrification race to supply final energy.

Electrification is the more consequential race today. It is the primary solution to displace 60% of fossil fuels and emissions, as well as the way to substitute 75% of energy imports.

Electrification is a larger market opportunity. Global revenues of key electrification technologies such as EVs and heat pumps are already three times those of solar panels and wind turbines, and are projected by the IEA to be eight times larger by 2035.

Electrification hits home for consumers. While renewables can make electricity cheaper, electrification upgrades the everyday technologies households rely on—cars, heating, and control systems—delivering better value and greater savings.

Global leadership is shifting through electrification. China is pulling ahead—electrifying by 10 percentage points each decade. This growing domestic demand is laying the foundation for its global manufacturing dominance. Meanwhile, the US and Europe have remained stuck at just over 20% electrification since 2008.

Today’s energy debate is largely missing electrification. Public debate, government targets, and corporate plans are focused on renewables. Electrification is too often an afterthought.

It’s time to reframe the conversation. Electrification is not a downstream detail—it is the main stage of the transition. This article is the first in a series to put it at the centre of the transition story.

The two key races of the energy transition

The energy transition is often described as a shift in primary energy supply from fossil fuels to renewables. While broadly accurate, this characterization captures only part of the picture. It frames the transition largely as a matter of production—of changing how energy is produced—while overlooking an equally important transformation in how energy is consumed. This is not solely a supply-side story; it is a fundamental reordering of energy demand as well.

At the heart of this transformation lie two overlapping but distinct contests, each redefining a major dimension of the global energy system.

The Renewables Race is the competition to generate electricity. The disruptive technologies are solar and wind, augmented by battery storage; and the incumbents are coal and natural gas. It is the more widely recognised of the two races—frequently discussed in public debate, policy circles, and media coverage. It is also the race where progress is easiest to track, with falling costs, record-breaking deployment, and growing shares of clean electricity in many grids.

The Electrification Race is less conspicuous, but no less pivotal. It is the competition to supply final energy demand for heat, mobility, and other services. In this race, electrons are the disruptor, and the incumbents are molecules: fossil fuels delivered directly to homes, vehicles, and factories. If the renewables race changes how electricity is made, the electrification race changes how electricity is used in the energy system.

Together, these two races define the contours of the transition.

Both races are well underway, though their progress is uneven. One is at an earlier stage but accelerating rapidly; the other is more advanced, yet progressing more gradually.

Solar and wind generation—the main driver of clean electricity supply growth—are still in the early phases of adoption, providing just 15% of electricity generation in 2024. But their momentum is striking: generation rose by 17% in 2024, and they accounted for 57% of the increase in global electricity supply. At their current pace of growth, they are on track to supply all new electricity demand within the next few years.

Electrification, by contrast, is further along but growing less rapidly. Electricity has been steadily rising for decades and now accounts for around 22% of final energy consumption. Electricity demand grew by 4% in 2024, and electricity supplied 40% of the growth in final energy demand. If trends hold, it could feasibly cover the entirety of that growth by the end of the decade.

In both races, the pattern is consistent: disruptive technologies are expanding faster than the systems in which they operate. As a result, their share of the market keeps rising.

The outcome of the energy transition depends on both races. Their pace—and their alignment—will shape not only the speed of decarbonization but also the very structure of the global energy system for decades to come.

Electrification is the more consequential race today

Both races matter, and both are advancing in parallel. But electrification is arguably the more significant race today. As we’ll explore in this section, it addresses the larger share of energy use—around 60% of final demand—and ultimately defines the reach of renewables. Without electrification, clean electricity cannot displace fossil fuels at the point of use.

Electrification has far-reaching implications, from reducing dependence on fossil fuel imports to cutting emissions. It also represents the biggest opportunity for domestic value creation—through infrastructure, supply chains, and industrial capacity—and the most direct source of consumer benefit, from lower energy expenditure to higher-value products.

Countries leading on electrification, such as China and Vietnam, are pulling ahead not only in deployment, but also in manufacturing and trade. Across energy, the economy, and geopolitics, electrification has become the more consequential race.

More energy in scope

The most immediate and obvious reason to focus on electrification is scale. It targets a much larger share of the energy system than renewables alone—and ultimately sets the ceiling for how far renewables can go.

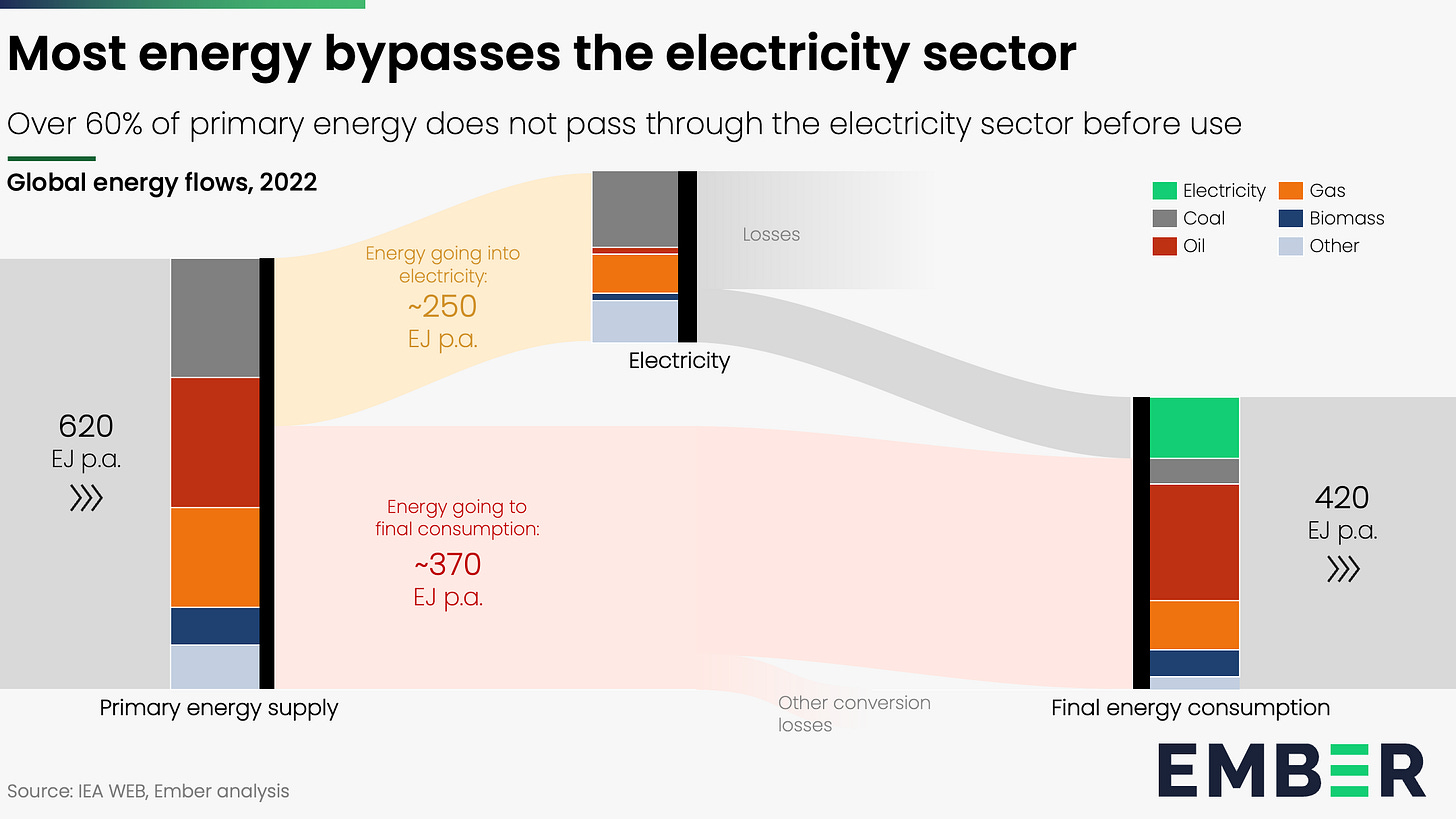

Today, around 60% of primary energy supply flows through to final consumption in transport, buildings, and industry. No matter how abundant clean electricity becomes, it cannot displace fossil fuels in these sectors unless end uses are electrified. Fossil fuels still supply 95% of final energy in transport, 56% in industry, and 37% in buildings.

This broader scope also brings more emissions into view. Over 60% of global energy-related emissions come from final energy use. Without widespread electrification, these emissions would remain largely untouched.

More independence to be gained

Electrification is not only broader in scope—it is also one of the most powerful levers for strengthening energy security, as we set out in ‘Energy security in an insecure world’. Most fossil fuel imports are used directly in final consumption, not electricity generation. In energy terms, over three-quarters of net fossil fuel imports are consumed in transport, buildings, and industry—sectors that can increasingly be electrified.

This makes electrification a uniquely strategic opportunity: it directly cuts demand for imported fuels by replacing fossil molecules with domestic electrons. Of course, to fully realise this potential, it must go hand-in-hand with the expansion of renewables power. Together, they allow countries to substitute local, renewable electricity for imported oil, gas, and coal, paving the way for long-term energy sovereignty.

More money to be made

Electrification is also a commercial story. End-use energy services such as transport and heating are sectors where households and businesses already spend trillions of dollars each year. These are large, high-value, generally high-margin markets. Unlike bulk energy supply, which is capital-intensive and commoditized, demand-side technologies sell directly to consumers and command stronger pricing power.

This difference is already evident in market size: the combined dollar value of the electric vehicle and heat pump markets is now three times larger than that of wind turbines and solar panels. This is despite the fact that wind and solar already account for over 90% of new global power capacity additions, while electric vehicle and heat pump sales still make up less than a quarter of total car and heating system sales—currently around 20% and 12%, respectively. The gap is set to widen. The IEA projects that by 2035, these end-use markets will outpace supply markets by a factor of eight.

Margins tell a similar story. Wind and solar manufacturers typically operate with low single-digit gross margins, with slightly better returns for project developers and installers. By contrast, firms producing electrification technologies—such as Tesla, BYD, Daikin, and Lennox—tend to post double-digit gross margins. Their advantage is simple: they are closer to the end customer, and, as in many sectors, proximity to the user translates into pricing power.

Electrification also presents the larger export opportunity. Global trade in batteries—driven primarily by electric vehicles—is already valued at an estimated $160 billion, surpassing the combined trade value of wind and solar technologies, which together total around $68 billion. Electric heating and cooling equipment exports are also larger, as is the $72 billion export market for electric motors. As electrification accelerates, these gaps will grow, opening up high-value export markets for companies with the right capabilities.

Perhaps most significantly, much of the supply chain needed for electrification has yet to be built, as pointed out in IEA’s annual ETP report. Take solar, for instance: current manufacturing capacity already covers about 70% of expected demand through 2035 and beyond. For wind, it’s around 50%. But for electric vehicles and heat pumps, it’s only 20–30%. While the entire energy system is expanding, electrification—across transport, buildings, and industry—still requires a massive buildout of production capacity, installation capabilities, and supporting infrastructure. This is where the largest amount of growth still lies—and where the greatest commercial opportunities remain.

More impact on final consumers

For those who already have electricity, electrification of end-use consumption is the part of the energy transition that matters most because it’s where the benefits are direct, tangible, and personal. Electrification can deliver lower spending, better products, and improved day-to-day life.

The potential financial impact is significant. Households in the U.S. and EU currently spend about a sixth of their income on energy-related costs. Renewables can help households save money. By lowering wholesale prices, or through distributed generation, they can reduce energy bills by hundreds of dollars per year. Electrification goes even further: by cutting spending on transport and heating fuels, and reducing equipment and maintenance costs, it has the potential to save households thousands of dollars annually—equivalent to 3–5% of typical Western household income.

But the case for electrification isn’t just economic. It also improves quality of life. Renewables deliver the same electrons as fossil fuel power generation; the consumer experience remains unchanged. Electrification delivers something more transformative for people’s daily life. Electric vehicles are quieter, smoother, less pollutive, and more convenient as they can charge at home. Heat pumps provide not just heating without toxic combustion byproducts, but also efficient cooling, with smart controls and consistent comfort.

These are upgrades people notice. They go beyond saving money and enhance daily life. This is what surveys show as well: people who switch to EVs and heat pumps do not want to switch back and recommend the technology to others. That’s why any serious political push to accelerate the energy transition should focus on electrification. It’s where the benefits are clearest and most immediate.

More geopolitical differentiation

While renewable energy deployment has advanced across much of the world, progress on electrification has been far more uneven. That divergence is creating a new class of energy leaders—and leaving others behind.

Over the past decade, many countries have expanded wind and solar generation at pace. From Germany to Chile, Morocco to Turkey renewable shares in electricity generation have risen significantly.

But electrification is different. The electrification rate has barely shifted in most of the OECD, typically rising by just one or two percentage points since 2010; but it has risen notably across much of Asia, led by an increase in China of nearly 10 percentage points.

This growing divide becomes clearer when countries are grouped by their progress on both renewables and electrification. As shown in the image below, four broad categories have emerged over the past decade. Many countries are renewables accelerators—they’ve added clean electricity supply but have not significantly expanded electricity’s role in the wider energy system. A few, however, stand out as electrostate builders: nations that have moved decisively on both fronts.

China is the clearest example of this latter group. It has rapidly scaled wind and solar, while also expanding electrification by over 10 percentage points over the past decade. It hasn’t just added renewable electricity, it has also put it to work across transport, buildings, and industry. That positions the country in the top-right quadrant of the transition map: high deployment on both supply and demand of electricity.

These electrostate builders are not just deploying electrotech—they are also producing it at scale. China manufactures 70% of the world’s EVs, over 75% of batteries, and 80% of solar panels. Other rapidly electrifying countries, such as Vietnam, are expanding their presence across several of these markets as well. What enabled this was not just low-cost manufacturing or policy support, but strong domestic demand. By building large internal markets through electrification policies, these countries create reliable offtake for their own industries—providing the scale, stability, and experience needed to compete globally.

While many Western countries led early on renewables, few have followed through with the necessary push on electrification. That is the central lesson for any country aiming to become an electrostate: renewables are necessary, but not sufficient. Without electrification, clean electricity cannot replace fossil fuels across the wider economy. And without strong domestic markets, it is difficult to build globally competitive supply chains. Many countries already have the renewable momentum to lead. Electrifying at scale and with urgency would turn this momentum into lasting industrial and geopolitical advantage.

Electrification is overlooked

Despite its central role in the transition, electrification has received surprisingly little attention. Public interest remains limited: Google search trends show that topics related to “renewables” currently attract four times more traffic than “electrification.” And when electrification does enter the conversation, it is usually in narrow terms, centred on electric vehicles, rather than as a systemic shift across transport, buildings, and industry. This is an area where holistic thinking is necessary.

This imbalance is reflected in policy as well. At the COP climate conferences, electrification has never made it into the final agreement text, though renewables have been mentioned since COP27 in 2022. Most national climate plans (NDCs) include targets or strategies related to renewables and are mentioned in NDCs of 144 countries. In contrast, electrification is often addressed vaguely or not at all. Only 81 NDCs mention the theme, and typically with a focus on expanding energy access rather than shifting existing energy demand to electricity. Specific technologies like electric vehicles and heat pumps appear in just a few dozen plans.

The private sector shows a similar pattern. Corporate strategies, investor communications, and green finance frameworks regularly highlight renewable energy but often overlook the electrification of end use. As a result, the single most important lever for scaling the impact of electrotech—getting more renewable electricity into the real economy—has yet to receive the focused, system-wide attention it requires.

Time to change the conversation

Electrification is not a side issue in the energy transition but a central driver. It shapes how far renewables can reach, how much emissions can fall, and how the transition delivers economic and geopolitical returns. Yet it goes underappreciated.

That is no longer tenable. Countries that treat electrification as a core national strategic goal—such as China—are not just decarbonizing faster. They are building the industrial foundations and export capabilities that will define leadership in the next energy era. Others risk being left behind.

If the goal is to build energy systems that are resilient, low-cost, and high-performance, then electrification must move from the margins to the centre. And that shift begins by changing how we talk about the transition.

This is the first note in a series of articles that aims to do just that.

Gents, this is one of the best things I've read in months. Great perspective here. Well done.

A point I'd love to see addressed further is the impact of existing extensive electrification on this comparison between states. In a broad sense China is about where the USA was when FDR launched the Rural Electrification Program in the 30s and 40s. I'd posit that China's or Viet Nam's or Bangladesh's massive growth in electrification is due to being late adopters of extensive electrification. Now being new to teh game they can take advantage of new technologies from the get go while the USA, Canada, the EU etc have legacy systems that work well and exist as part of an integrated whole.